What's Juneteenth?

the holiday many of us learned about way too late

It was a little over one hundred degrees outside, humidity hovered just north of 80%, and I was about to go onstage to address a crowd of around three hundred people in a button up shirt and a pair of slacks. I was the only non-person of color at the park. A nice woman handed me a glass of lemonade before I took the stage and thanked me for coming to talk to their community at their annual celebration.

“What are we celebrating?” I asked.

“It’s Juneteenth,” she told me with an odd look. I nodded and gave her my best “of course,” face. I had no idea what she was talking about. The year was 2012. I was 34 years-old.

I grew up in the south. In fact, I had spent the past three years living in rural Georgia in a town that became a central shipping point for the Confederate army. Soldiers took over the local women’s college and turned the building into officer quarters and a hospital. No one celebrated Juneteenth, which is interesting given their most famous resident.

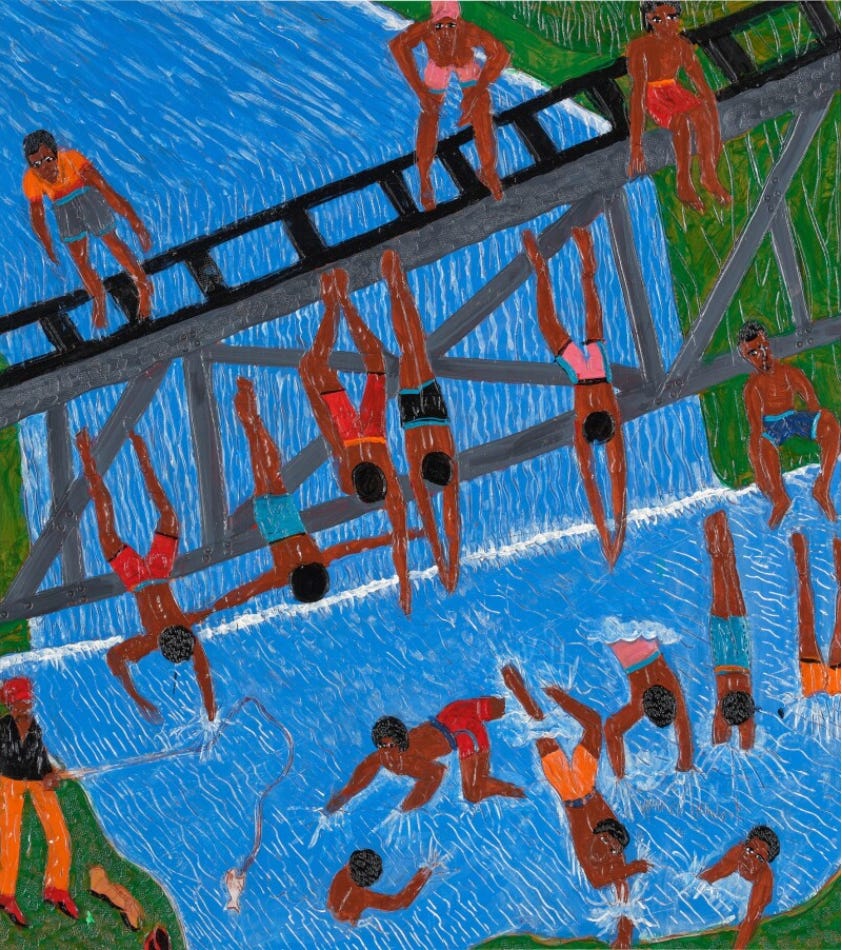

I met Winfred Rembert while living in Georgia. We had a nice lunch one afternoon in a quaint Southern setting, the type that can only be found in Georgia (Spanish moss in the trees, chess pie, and the sweetest tea you’ve ever put to your lips). He recounted a memory of his life in that little one-stoplight town in the middle of the cornfields, one that I’ll never forget as he told it. It’s recounted in a Sotheby’s article about his life and work:

“…while fleeing a white mob during a march in Americus, he was arrested for stealing a car and beaten in jail. He escaped but was shortly recaptured by the police. Then a lynch mob abducted him and locked him in the trunk of a car. They drove him to a tree, hung him by his feet and attempted to mutilate his genitals. While Rembert survived, he was left with lifelong pain in his groin and ultimately incarcerated for ten years.”

Sitting a block from the tree while he told the story was surreal. You could tell he felt the same. He hadn’t been back in some time.

Back at the park I found myself sweating out a tall glass of lemonade while talking to a crowd of folks that were probably wondering why I was there about as much I was wondering why they were there. I was working on a large arts initiative, and I sincerely wanted to make sure that it was a community wide effort, not something they did on “that” side of town.

I’d grown up in this community, one literally divided in half by a set of railroad tracks, the white (wealthier) community on one side, everyone else on the other. It wasn’t so much that way in 2012, but it also wasn’t all that far removed.

After giving my little speech, I walked around talking to folks. Some of them were curious about what this art project was all about, but most just wanted to make sure that their pond was restocked with fish annually to give the local kids something fun to do after school.

At some point, I ran into a few old friends from high school. It had been over fifteen years since we’d seen each other, but we caught up pretty quickly. I gathered up the courage to ask one of them, a former football team mate, what we were all doing out in the sun together.

“What’s Juneteenth?”

He didn’t tell me, just laughed at my expense. That’s okay. I deserved it.

Now four years after it’s become a national holiday, I’m baffled at the number of people who still don’t know anything about the celebration. At this point, it’s willful ignorance, a trait I learned a lot about growing up in the South.

However, that sentiment will die out. The right and the just will prevail over the course of time. Most of us would prefer not to have to take two steps back for every three steps forward, but that is our way. Maybe this next generation can help us speed up the path towards a better future.

Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year. Ours is not the struggle of one judicial appointment or presidential term. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part. — John Lewis

Happy teenth everybody!

Appreciate you reading. If it hits home, consider sharing it—and if you want more like it, subscribing keeps us in touch.

a little extra …

If you dig the image above, you should look for more of Winfred’s work. His medium was leather. It was a cross between Native American leather-working and Clementine Hunter’s paintings. The one below is called The Curvey. It’s the watering hole Winfred use to go to when he was playing hooky from school.

🤍