Book Notes: American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America

or proof that you aren't suffering from an existential crises and you can just hate where you live

Imagine if you will, the year is 2040, and Ron DeSantis is celebrating his fourth consecutive landslide victory as President of the Conservative Federation of States. The vote was held amongst the governors of each state after their selection and appointment by Mr. DeSantis, as is now customary. Riots in the streets of Austin, TX., Atlanta, GA., and New Orleans, LA. were quickly put down by the local militias with only a few hundred fatalities reported this election cycle.

Elections in The Free Federation of York also came to a close this afternoon as the historic electoral college met to decide the leader of that loose coalition stretching from New England, across the Great Lakes to the border of western Wisconsin. Turnout swelled this year to a whopping 8% of eligible voters.

On the western border, the Socialist Republic of the Pacific will have its regular elections on Holiday Day, a day to celebrate all holidays equally to ensure no implicit advantage to any individual celebration. Votes must be texted in on your government-provided device (sponsored by Google) no later than midnight to be counted. Although, the Free Peoples of Los Angeles have received a twelve-hour extension to the deadline to ensure their annual cannabis festival attendees do not miss the opportunity to participate. 😶🌫️

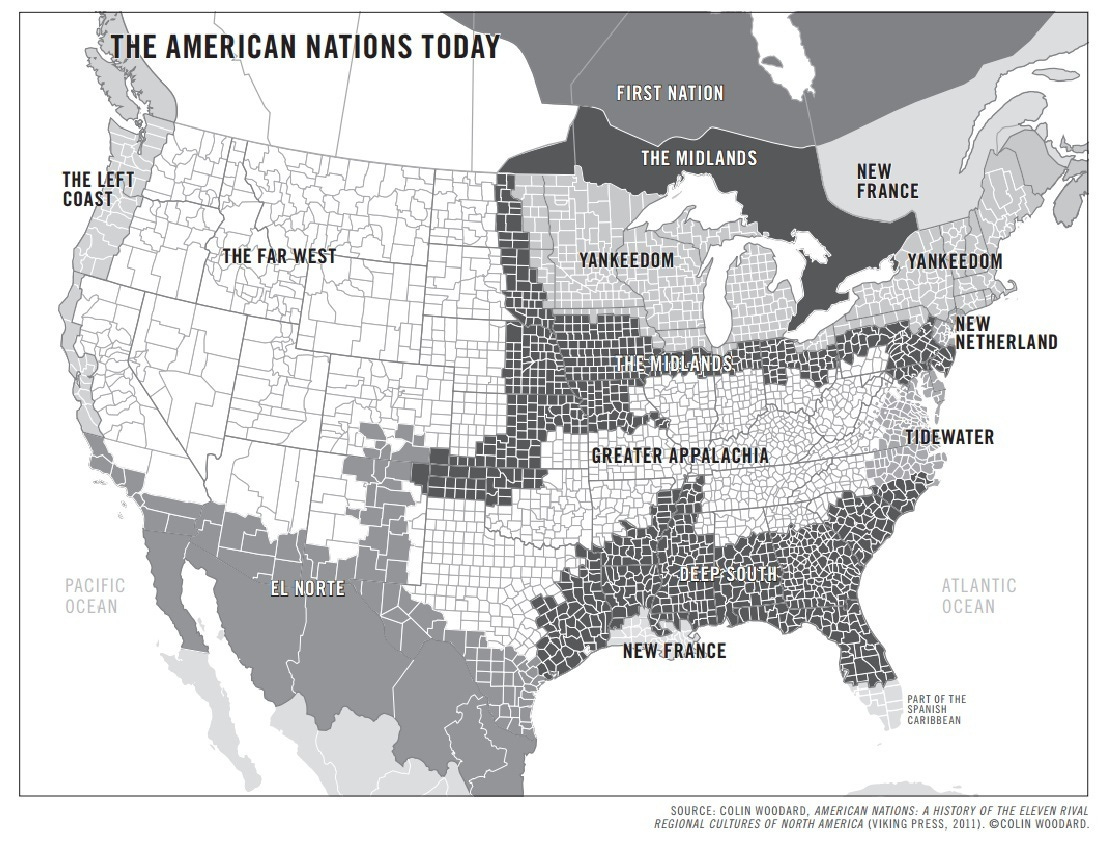

So, it’s only kinda funny. American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America written by Colin Woodard painted a grim future for the United States by highlighting our tumultuous past. Originally published in 2011, Woodard was heralding a systemic problem in our country that has existed since before its founding. We may be one United States, but we are a country of nations. Take a look at the breakup and definition of each individual area.

Broken into eleven different tribes, if you will, he charts the progress of immigration that started in the colonial era through to our current (2011) status. Although there have been many shakeups in the past 11 years, with economics forcing people out of some states and into others, I believe Woodard would argue that his thesis still holds.

…the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later. (pg. 16)

I’m not an advocate of separating our country into alternative nations, furthering the divide culturally, that has become such a standard discourse in day-to-day life. Moreover, I think it’s important to point at it, and remind ourselves that this is not the first time, nor the last that it will rear its ugly head.

As much detail as Woodard goes into about the various nations, he spends a good deal of his time setting up, what I’ll call the heavyweights, Yankeedom, and the Deep South. In modern cultural/political dogma you could easily lump the Left Coast, New Netherland, and Yankeedom together. In a similar fashion, I can see a pairing between Greater Appalachia, Tidewater, and the Deep South. In reference to Yankeedom, Woodard says:

It has been locked in nearly perpetual combat with the Deep South for control of the federal government since the moment such a thing existed. (pg. 5 YD)

A cursory review of American history shows this theory of shifting political forces to appear true. I don’t know that you could point to two ideologically opposed forces that have lived as peacefully side by side. Perhaps the occasional spat between the two superpowers keeps the pressure low enough to prevent an eruption, but there have been a number of shifts over the past decade that have really increased the volume between the opposing forces.

Woodard, a Yankee by birth says this about the nation of Yankeedom:

From the outset, it was a culture that put great emphasis on education, local political control, and the pursuit of the “greater good” of the community, even if it required individual self-denial. (pg. 5 YD)

About the Deep South, he is less flowery.

…the region has been the bastion of white supremacy, aristocratic privilege, and a version of classical Republicanism modeled on the slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was a privilege of the few and enslavement the natural lot of the many. (pg. 9 Deep South)

Here’s the thing, as a Deep Southerner by birth, I can’t argue against the picture he paints. It doesn’t mean that I like it, or that I identify as a person that celebrates this heritage. In fact, these very principles of the region caused me to reconsider where I call home. I don’t deny my birthplace, but I don’t have to like it either.

Not every page of the book provides a glowing report of the history of Yankeedom and its allies. There is an excellent section that details the scheme between Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton to devalue the IOUs paid to revolutionary soldiers, that is until their friends had bought them all up at a fraction of their value. They then paid face value on all the war bond notes in gold and silver. No one side has a clean record of humanitarian or societal aid.

However, it is quite clear as defined by multiple accounts within the book, that the origins of nearly every major conflict, policy, law, and election have been affected by cultural battles between what we now consider the left and the right. Woodard traces this history from its origins through the current culture wars we are experiencing again today.

Many whites in Appalachia, Tidewater, and the Deep South became further entrenched in a Southern evangelical worldview that resisted social reform or the lifting of cultural taboos, and increasingly sought to break down the walls between church and state so as to impose their values and moral code on everyone else. (p. 278)

Although they may seem to go together like oil and water for some, white nationalism has found a home in the evangelical movement in this country. We read about it (who am I kidding, you guys read about it), or most watch these stories on the news nightly. Whether you are watching pro or anti-white nationalist press, it is most assuredly the underbelly of the conversation. If there is a fuel that could push us over the brink of becoming a shattered nation like the former U.S.S.R, it is the white nationalist movement.

The majority of Yankees, New Netherlanders, and Left Coasters simply aren’t going to accept living in an evangelical Christian theocracy with weak or nonexistent social, labor, or environmental protections, public school systems, and checks on corporate power in politics. Most Deep Southerners will resist paying higher taxes to underwrite the creation of a public health insurance system; a universal network of well-resourced, unionized, and avowedly secular public schools; tuition-free public universities where science—not the King James Bible—guides inquiry; taxpayer-subsidized public transportation, high-speed railroad networks, and renewable energy projects; or vigorous regulatory bodies to ensure compliance with strict financial, food safety, environmental, and campaign finance laws. (p. 316 - 317)

Both sides have their lines, and until recently we battled it out in good faith, mostly. Now, in a world where reality is definable, where winning is the goal and not the result of a sound argument (as I discussed here), and where those who disagree with you are seen only as evil, the precipice could be closer than we think. From the final chapter of Woodard’s book written in 2011.

We won’t hold together if presidents appoint political ideologues to the Justice Department or the Supreme Court of the United States, or if party loyalists try to win elections by trying to stop people from voting rather than winning them over with their ideas. (p. 318)

Woodard’s breaking point is our reality.

The good news, if there is any? None of this is new. These arguments are as old as our country, and our ability to recognize them as such should take away a little bit of their power. It should reduce our collective fear. It must give us the opportunity to talk to one another again. Or, perhaps it's too late. If so, I hope you like where you live. I know I do … now. :)

QUOTES:

A state is a sovereign political entity like the United Kingdom, Kenya, Panama, or New Zealand, eligible for membership in the United Nations and inclusion on the maps produced by Rand McNally or the National Geographic Society. A nation is a group of people who share—or believe they share—a common culture, ethnic origin, language, historical experience, artifacts, and symbols. (pg. 3)

From the outset, it was a culture that put great emphasis on education, local political control, and the pursuit of the “greater good” of the community, even if it required individual self-denial. (pg. 5 YD)

It has been locked in nearly perpetual combat with the Deep South for control of the federal government since the moment such a thing existed. (pg. 5 YD)

New Amsterdam was from the start a global trading society: multi-ethnic, multi-religious, speculative, materialistic, mercantile, and free trading, a raucous, not entirely democratic city-state where no ethnic or religious group has ever truly been in charge. (pg. 6)

Pluralistic and organized around the middle class, the Midlands spawned the culture of Middle America and the Heartland, where ethnic and ideological purity have never been a priority, government has been seen as an unwelcome intrusion, and political opinion has been moderate, even apathetic. (pg. 6)

…aimed to reproduce the semifeudal manorial society of the English countryside, where economic, political, and social affairs were run by and for landed aristocrats. (pg. 7 Tidewater)

…responsible for many of the aristocratic inflections in the Constitution, including the Electoral College and Senate. (pg. 7 Tidewater)

…culture had formed in a state of near-constant ware and upheaval, fostering a warrior ethic and a deep commitment to individual liberty and personal sovereignty. intensely suspicious of aristocrats and social reforms alike, these American Borderlanders despised Yankee teachers, Tidewater lords, and Deep Southern aristocrats. (pg. 8 Greater Appalachia)

…the region has been the bastion of white supremacy, aristocratic privilege, and a version of classical Republicanism modeled on the slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was a privilege of the few and enslavement the natural lot of the many. (pg. 9 Deep South)

Down-to-earth, egalitarian, and consensus-driven, the New French have recently been demonstrated by pollsters to be far and away the most liberal people on the continent. (pg. 9)

Split by an increasingly militarized broader, El Norte in some ways resembles Germany during the Cold War. (pg. 10)

…retained a strong strain of New England intellectualism and idealism even as it embraced a culture of individual fulfillment.

…the colonization of much of the region was facilitated and directed by large corporations headquartered in the distant New York, Boston, Chicago, or San Francisco, or by the federal government. (pg. 12 Far West)

…the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later. (pg. 16)

…becoming a member of a nation usually has nothing to do with genetics and everything to do with culture. One doesn’t inherit a national identity the way one gets hair, skin, or eye color; one acquires it in childhood or, with great effort, through voluntary assimilation later in life. (pg. 18)

Between 1598 and 1794 the Spanish established at least eighteen missions in what is now the state of New Mexico, twenty-six in what is now Texas, eight in Arizona, and twenty-one in Alta California—in the process founding what have since become the cities of Tucson, San Antonio, San Diego, and San Francisco. (p. 29 EN)

…the people of El Norte were seen as being more adaptable, self-sufficient, hardworking, aggressive, and intolerant of tyranny. (p. 31 EN)

On ranches and mission lands, cattle hands spent long periods in remote areas far from the surveillance of superiors, and non-neophytes could move from ranch to ranch in search of the best conditions; indeed, it was these independent, self-sufficient, mobile ranch hands who developed the legendary cowboy culture of the American West. (p. 32 EN)

The Spanish introduced houses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the New World, along with the clothes, tools, and skills to ranch them, building the common foundations of all subsequent cowboy cultures from the huasos of Chile to the cowboys of the American West. (p. 32 EN)

The first American cowboys were, in fact, Indians. (p. 33 NF)

He regarded the Indians as every bit as intelligent and human as his own countrymen, and thought cross-cultural marriage between the two peoples was not only tolerable but desirable. (p. 35 referring to Champlain)

In reality, the first lasting English colony in the New World was a hellhole of epic proportions, successful only in the sense that it survived at all. (p. 44 NF)

…in the winter of 1609-1610 food ran out again, and the settlers were forced to eat rats, cats, snakes, and even their boots and horses. They dug but the bodies of those who’d died and ate those. (p. 45 TW)

…the Virginia Company’s plan was based on the faulty assumption that the Indians would be intimidated by English technology, believe their employers were gods, and submit, Aztec-like, to their rule. The Indians, in fact, did none of these things. (p. 45 TW)

Between 1607 and 1624, 7,200 colonists arrived; although only 1,200 survived, for every Virginian who died, two more came to take his or her place. (p. 46 TW)

White and black settlers were not segregated, and at least some blacks enjoyed the few civil rights available to commoners. (p. 48 TW)

…Church of England (the “Anglican” church, rebranded “Episcopal” in America after the Revolution). (p. 51 TW)

On the lord’s death, virtually everything passed to his firstborn son, who had been groomed to rule; daughters were married off to the best prospects; younger sons were given a small sum of money and dispatched to make their own way as soldiers, priests, or merchants. One gentleman said children were treated like a litter of puppies: “Take one, lay it in the lap, feed it with every good bit, and drown [the other] five!” (p. 51 TW)

While the Yankee elite generally settled their disputes through the instrument of written laws, Tidewater gentry were more likely to resort to a duel. (p. 53 TW)

They emulated the learned, slaveholding elite of ancient Athens, basing their enlightened political philosophies around the ancient Latin concept of libertas, or liberty. This was a fundamentally different notion from the Germanic concept of Freiheit, or freedom, which informed the political thought of Yankeedom and the Midlands. (p. 54 TW)

…“freedom” was a birthright of free peoples… (p. 54 TW)

…most humans were born into bondage. Liberty was something that was granted and was thus a privilege, not a right. (p. 55 TW)

…highborn families saw themselves as descendants not of the “common” Anglo-Saxons, but rather of their aristocratic Norman conquerors. (p. 55 TW)

…Virginian John Randolph would explain decades after the American Revolution. “I love liberty; I hate equality.” (p. 55 TW)

Slave traders offered a solution to this shortage, one developed on the English islands of the Caribbean and recently introduced in the settlements they’d created in the Deep South: the purchase of people of African descent who would become the permanent property of their masters, as would their children and grandchildren. (p. 56 TW)

“The South was not founded to create slavery; slavery was recruited to perpetuate the South.” (p. 56 TW)

The Pilgrims and, to a greater extent, the Puritans came to the New World not to re-create rural English life but rather to build a completely new society: an applied religious utopia, a Protestant theocracy based on the teachings of John Calvin. (p. 57 YD)

While Tidewater was settled largely by young, unskilled male servants, New England’s colonists were skilled craftsmen, lawyers, doctors, and yeoman farmers; none of them was an indentured servant. (ps. 58 - 59 YD)

If everyone was expected to read the Bible, everyone had to be literate. (p. 61 YD)

Unlike the settlers in New France, the Puritans regarded the Indians as “savages” to whom normal moral obligations—respect of treaties, fair dealing, forgoing the slaughter of innocents—did not apply. (p. 62 YD)

In 1602, they invented the global corporation with the establishment of the Dutch East India Company, which soon had hundreds of ships, thousands of employees, and extensive operations in Indonesia, Japan, India, and southern Africa. (p. 67 NN)

While in exile in Amsterdam, John Locke composed his A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), which argued for a separation of church and state. (p. 67 NN)

“not force poeple’s consciences but allow everyone to have his own belief, as long as he behaves quietly and legally, gives no offense to his neighbors, and does not oppose the government.” (p. 70 NN)

Jan Aertsen Van der Bilt arrived as an indentured servant in 1650; his third great-grandson, Cornelius—born on Staten Island—would make the “Vanderbilt” family one of the wealthiest in history. (p. 71 NN)

…full-on slavery was introduced to what is now the United States not by gentlemen planters of Virginia or South Carolina but by the merchants of Manhattan. (p. 71 NN)

While everyone knows that the English-controlled colonies rebelled against the tyrannical rule of their distant king, few realize they first did so not in the 1770s, but in the 1680s. (p. 73)

In court, Puritans faced Anglican juries and were forced to kiss the Bible when searing their oaths (an “idolatrous” Anglican practice) instead of raising their right hand, as was Puritan custom. (p. 75)

…they were the sons and grandsons of the founders of an older English colony: Barbados, the richest and most horrifying society in the English-speaking world. (p.82 DS)

From the outset, Deep Southern culture was based on radical disparities in wealth and power, with a tiny elite commanding total obedience and enforcing it with state-sponsored terror. (p. 84 DS)

By imposing onerous property requirements for the right to vote, the great planters monopolized the island’s elected assembly, governing council, and judiciary. (p. 85 DS)

Their 1698 law declared Africans to have “barbarous, wild, savage natures” that made them “naturally prone” to “inhumanity,” therefore requiring tight control and draconian punishments. (p. 86 DS)

From the hell of the slave quarters would come some of the Deep South’s great gifts to the continent: blues, jazz, gospel, and rock and roll, as well as the Caribbean-inspired foodways today enshrined in Southern-style barbeque joints from Miami to Anchorage. (p. 88 DS)

The system’s fundamental rationale was that blacks were inherently inferior, a lower form of organism incapable of higher thought and emotion and savage in behavior. (p. 88 DS)

It is Middle America, the most mainstream of the continent’s national cultures and, for much of our history, the kingmaker in national political contests. (p. 92 ML)

…Quakers were considered a radical and dangerous force, the late-seventeenth-century equivalent of crossing the hippie movement with the Church of Scientology. (p. 92 ML)

They rejected the authority of church hierarchies, held women to be spiritually equal to men, and questioned the legitimacy of slavery. (p. 92 ML)

They didn’t study and obey scripture to achieve salvation, but instead found God through personal mystical experience—meaning that priests, bishops, and churches were superfluous. (p. 93 ML)

… German Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania. “We shall do to all men like as we will be done ourselves,” the protestors declared in 1712, “making no difference of what generation, descent or color they are.” (p. 97 ML)

A clan-based warrior culture from the borderlands of the British Empire, it arrived on the backcountry frontier of the Midlands, Tidewater, and Deep South and shattered those nations’ monopoly control over colonial governments, the use of force, and relations with Native Americans. (p. 101 GA)

When they did need cash, they distilled corn into a more portable, storable, and valuable product: whiskey, which would remain the de facto currency of Appalachia for the next two centuries. (p. 104 GA)

Justice was meted out not by courts but by the aggrieved individuals and their kin via personal retaliation. (p. 105 GA)

With the highlands of South Carolina and Georgia beginning to resemble the lawless frontiers of Scotland, leading Appalachian families responded in the familiar Borderlander fashion: they formed a vigilante gang to hunt the bandits down. They called themselves the Regulators… (p. 109 GA)

…it (American Revolution) was a profoundly conservative action fought by a loose military alliance of nations, each of which was most concerned with preserving or reasserting control of its respective culture, character, and power structure. (p. 115)

…new fees for the issuance of university diplomas and licenses to practice law were higher than those in Great Britain “to keep mean [lowborn] persons out of those institutions in life which they disgrace. (p. 117)

…David Hackett Fischer makes the case for there having been not one American War of Independence but four: a popular insurrection in New England, a professional “gentleman’s war” in the South, a savage civil war in the backcountry, and a “non-violent economic and diplomatic struggle” spearheaded by the elites of what I call the Midlands. / But there weren’t four neat struggles, one unfolding as the previous one concluded; rather, there were six very different liberation wars, one for each affected nation. (p. 125)

Until the Battle of Lexington, the Deep South’s all-powerful ruling class was ambivalent about fighting a war of liberation. (p. 133)

When the wars began, the only structure the colonies shared was a diplomatic body, the Continental Congress. (p. 141)

In the end, the U.S. Constitution was the product of a messy compromise among the rival nations. From the gentry of Tidewater and the Deep South, we received a strong president to be selected by an “electoral college” rather than elected by ordinary people. (p. 148)

The Yankees ensured that small states would have an equal say in the Senate, with the very populous state of Massachusetts frustrating Tidewater and the Deep South’s desire for proportional representation in that chamber; Yankees also forced a compromise whereby slave lords would be able to count only three-fifths of their slave population when tabulating how many congressmen they would receive. (p. 149)

Unfettered individual pursuit of absolute freedom and property accumulation, they (New Englanders) feared, would destroy community ties, create an aristocracy, and enslave the masses, resulting in a tyranny along the lines of the British or the Deep South. (p. 162)

Democrats in this era (1850) rejected the notion that governments had a moral mission to better society, either through assimilating minorities or eliminating slavery. (p. 187)

“Hoosier”— a Southern slang term for a frontier hick—was adopted as a badge of honor by the Appalachian people of Indiana. (p 190)

Appalachian people everywhere distrusted political parties, seeing them as cartels of powerful interests, and voted for whichever one appeared to advocate for ordinary individuals. (p. 193)

His (Andrew Jackson) principles—minimal government, maximum freedom for individuals, aggressive military expansion, white supremacy, and the right of each American nation to uphold its customs without the interference of others—earned him few friends in the Midlands and Yankeedom. (p. 196)

Since the United States had banned their importation (slaves) in 1808, planters in the new Gulf states and territories began purchasing them from counterparts in tidewater and Appalachia. (p. 201)

Being “sold down the river” originally referred to slaves being sold by Appalachian people in Kentucky and Tennessee to downriver plantation owners in the Deep South. (p. 202)

Southern Baptist and Methodist preachers broke with their northern counterparts to endorse slavery… (p. 203)

Under Mexican law, Anglo-Americans were unwelcome, but Texas officials were desperate enough for settlers to look the other way. (p. 209)

Deep Southern newspapers covered the war intensively, casting it as a racial struggle between barbarous Hispanics and virtuous whites, inspiring thousands of Southern adventurers to cross into Texas to join the fighting. (p. 211)

Curiously, further annexations were rejected because of the opposition of Deep Southern leaders, who feared being unable to assimilate the more densely populated, racially missed central and southern states of Mexico. / … warned Senator John Calhoun, “I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race.” (p. 214)

The primary reason is that the majority of the Left Coast’s early colonists were Yankees who arrived by sea in the hopes of founding a second New England on the shores of the Pacific. (p. 216 LC)

When Puget Sound became desperate for women in the h1860s—white men outnumbered white women by a nine-to-one ratio—local leaders recruited 100 single New England women and shipped them to Seattle; to be a descendant of one of these settlers still has Mayflower-like cachet there. (p. 219 LC)

Arriving by sea, the Yankees congregated in Santa Barbara and Monterey, learned Spanis, converted to Catholicism, took Mexican citizenship and spouses, adopted Spanish versions of their names, and respected and participated in local politics. (p. 219 LC)

The Civil War was ultimately a conflict between two coalitions. On one side was the Deep South and its satellite, Tidewater; on the other, Yankeedom. (p. 224)

When nineteenth-century Deep Southerners spoke of defending their “traditions,” “heritage,” and “way of life,” they proudly identified the enslavement of others as the centerpiece of all three. (p. 227)

Lincoln did not even appear on the ballot in Deep Southern-controlled states. (p. 230)

“The attack on Fort Sumter has made the North a unit,” Stickles wrote the federal secretary of war. “We are at war with a foreign power.” (p. 232)

…the Confederate aim was to create “a sort of Patrician Republic” ruled by a people “superior to all other races on this continent.” (P. 235)

In Arkansas, Deep Southerners in the state’s lowland southeast threatened to secede after delegates from the Appalachian northwest blocked their proposal to leave the Union. (p. 237)

The people of Tidewater, the Deep South, and Confederate Appalachia resisted the Yankee reforms as determinedly as they could, and after Union troops withdrew in 1876, whites in the “reconstructed” regions undid the measures. Yankee public schools were abolished. Imposed state constitutions were rewritten, restoring white supremacy and adopting poll taxes, “literacy tests,” and other instruments that allowed white officials to deprive African Americans of the right to vote. (p. 238 - 239)

…by the early twentieth century, the people of the Far West would come to resent both the corporations and the federal government, seeing them as joint oppressors. By allying with the Deep South, their political leaders have managed to weaken federal stewardship of Far Western resources. Ironically, this has merely served to increase corporate dominance over their nation. (p. 251 FW)

Immigrants didn’t alter “American culture,” they altered America’s respective regional cultures. (p. 255)

Between 1830 and 1924 some 36 million people emigrated to the United States. They arrived in three distinct waves. The first—the arrival of some 4.5 million Irish, Germans, and British people between 1830 and 1860. / The second between 1860 and 1890, saw twice as many immigrants, largely from the same countries plus Scandinavia and China. The third wave, from 1890 to 1924, was the largest of all, with some 18 million new arrivals, mostly from southern and eastern Europe. / This third wave was cut short in 1924, when the U.S. Congress imposed quotas designed to protect the federation from the taint of “inferior races,” including Italians, Jews, and immigrants from the Balkans and East Europe. (p. 255)

They “freed” an oppressed people—the region’s enslaved blacks—but failed to provide the security or economic environment in which they might thrive. (p. 264)

The evangelical churches that dominated the three southern nations proved excellent vehicles for those wishing to protect the region’s prewar social system. (p. 264)

Appalachia’s staggering poverty—made worse by war and economic dislocation—created a situation in which many white Borderlanders found themselves in direct competition with newly freed blacks, who tended to be less deferential than those in the lowlands. The response was the creation of a secret society of homicidal vigilantes called the Ku Klux Klan. (p266)

Opposition to modernism, liberal theology, and inconvenient scientific discoveries occurred in pockets across the continent in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but only in the Dixie bloc did it represent the dominant cultural position, backed by governments and defended from criticism by state power. (p. 271)

During the 1920s, anti-evolutionary activists afflicted the entire federation, but they found lasting success only in Appalachia and the Deep South. Legislators in Florida, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas passed laws making it illegal to teach evolution in schools. (p. 272)

Political candidates often put the suppression of evolution at the center of their campaigns, while a revived KKK bristled against Darwin’s theory because it contradicted biblical arguments that God had created blacks as servile and inferior beings. (p. 272)

Many whites in Appalachia, Tidewater, and the Deep South became further entrenched in a Southern evangelical worldview that resisted social reform or the lifting of cultural taboos, and increasingly sought to break down the walls between church and state so as to impose their values and moral code on everyone else. (p. 278)

The culture wars of the 1990s and 2000s were in essence a resumption of the sixties-era struggle, with a majority of people in the four northern nations generally supporting social change and an overwhelming majority of those in the Dixie bloc defending the traditional order. (p. 281)

…the nations of the Dixie bloc have continued to promulgate policies that ensure they remain low-wage resource colonies controlled by a one-party political system dedicated to serving the interest of a wealthy elite. (p. 283)

The Nazis had praised the Deep South’s caste system, which they used as a model for their own race laws. (p. 289)

Indeed, Hitler and Emperor Hirohito did more for the development of the Far West and El Norte than any other agent in those regions’ histories. Long exploited as internal colonies, both nations were suddenly given an industrial base to help the Allies win the war. (p. 290)

Ultimately the determinative political struggle has been a clash between shifting coalitions of ethnoregional nations, one invariably headed by the Deep South, the other by Yankeedom. (p. 295)

In a flip-flop of enormous proportions, the Democrats had become the party of the Northern alliance, and the “party of Lincoln” had become the vehicle of Dixie-bloc whites. (p. 299)

The goal of the Deep Southern oligarchy has been consistent for over four centuries: to control and maintain a one-party state with a colonial-style economy based on large-scale agriculture and the extraction of primary resources by a compliant, poorly educated, low-wage workforce with as few labor, workplace safety, health care, and environmental regulations as possible. (p. 302)

…once in office, they focused on cutting taxes for the wealthy, funneling massive subsidies to the oligarchs’ agribusinesses and oil companies, eliminating labor and environmental regulations, creating “guest worker” programs to secure cheap farm labor from the developing world, and poaching manufacturing jobs from higher-wage unionized industries in Yankeedom, New Netherland, or the Midlands. (p. 303)

“I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.” Johnson told an aide hours after signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law. (p. 305)

…the Dixie coalition voted en masse against the civil rights and voting acts of the 1960s; for bans on union shop contracts in the 1970s; for lowering taxes on the wealthy and eliminating taxes on inherited wealth in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s; for invading Iraq in 2003; and for blocking health care and financial regulatory reform and increases in minimum wages in 2010. (p. 306)

By the end of his presidency (Bush 43)—and the sixteen-year run of Dixie dominance in Washington—income inequality and the concentration of wealth in the federation had reached the highest levels in its history, exceeding even the Gilded Age and Great Depression. (p. 308)

Like its superpower predecessors, the United States has built up a staggering external trade deficit and sovereign debt while overreaching itself militarily and greatly increasing both the share of financial services in national output and the role of religious extremists in national political life. Once the great exporter of innovations, products, and financial capital, the United States is now deeply indebted to China, on which it relies for much of what its people consume and, increasingly, for the scientists and engineers needed by research and development firms and institutions. (p. 314 -315)

The majority of Yankees, New Netherlanders, and Left Coasters simply aren’t going to accept living in an evangelical Christian theocracy with weak or nonexistent social, labor, or environmental protections, public school systems, and checks on corporate power in politics. Most Deep Southerners will resist paying higher taxes to underwrite the creation of a public health insurance system; a universal network of well-resourced, unionized, and avowedly secular public schools; tuition-free public universities where science—not the King James Bible—guides inquiry; taxpayer-subsidized public transportation, high-speed railroad networks. and renewable energy projects; or vigorous regulatory bodies to ensure compliance with strict financial, food safety, environmental, and campaign finance laws. (p. 316 - 317)

We won’t hold together if presidents appoint political ideologues to the Justice Department or the Supreme Court of the United States, or if party loyalists try to win elections by trying to stop people from voting rather than winning them over with their ideas. (p. 318)

THE NATIONS:

Yankeedom(YD): founded on the shores of Massachusetts Bay by radical Calvinists as a new Zion, a religious utopia in the New England wilderness.

New Netherland(NN): short-lived seventeenth-century Dutch colony that laid down the DNA for Greater New York City.

The Midlands(TM): founded by English Quakers, who welcomed people of many nations and creeds to their utopian colonies on the shores of the Deleware Bay

Tidewater(TW): fundamentally conservative region with high value placed on respect for authority and tradition and very little on equality and public participation in politics

Greater Appalachia(GA): rough, bellicose settlers from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands

Deep South(DS): founded by Barbados slave lords as a West Indies-style slave society, a system so cruel and despotic that it shocked even its seventeenth-century English contemporaries.

New France(NF): blends the folkways of ancien régime northern French peasantry with the traditions and values of the aboriginal people they encountered in northeastern North America

El Norte(EN): oldest of the Euro-American nations, dating back to the late sixteenth century, when the Spanish empire founded Monterrey, Saltillo, and other northern outposts

Left Coast(LC): a strip from Monterey, California, to Juneau, Alaska, including four decidedly progressive metropolises: San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver

Far West(FW): environmental factors trump cultural ones … conditions so severe that they effectively destroyed those who tried to apply the farming and lifestyle techniques used in Greater Appalachia, the Midlands, and other nations

First Nation(FN): boreal forests, tundra, and glaciers of the far north

TERMS:

Doctrine of First Effective Settlement: Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny they initial band of settlers may have been.

Patrón: an elite figure who undertook patriarchal responsibilities for their well-being

The Great Wagon Road: a well-improved trail from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, and from Georgia to colonial America through the Greater Appalachian region

Blackbirders: slave-catching bounty hunters who departed their captures to the plantations

Anathema: something or someone that one vehemently dislikes

Indolent: wanting to avoid activity or exertion; lazy

Acculturated: assimilate or cause to assimilate a different culture, typically the dominant one

Inerrancy: the belief that the Bible is free from error in matters of science as well as those of faith

The Fundamentals: a 12-volume attack on liberal theology, evolution, atheism, socialism, Mormons, Catholics, Christian Scientists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses edited by Appalachian Baptist preacher A. C. Dixon.